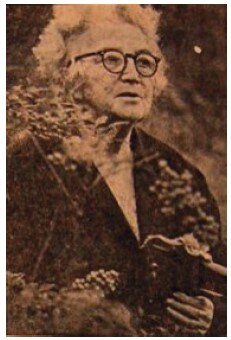

Dr. Bertram Whittier Wells, known as B.W. ,was a pioneer ecologist teaching at NC State University (then called NC State Agricultural College). He was one of the first generation of botanists that moved from the classification of plants to a holistic view of plants in the context of their environment. His encounter with the Big Savanah in 1920, a floral wonder on the coastal plain of NC, was the pivotal moment of his professional career. It opened his eyes and aroused his curiosity to the problems of plant ecology and focused his whole career on research into explaining why plants grew where they did and the discovery of their relationships in communities.

Wells chaired the Botany Department at NC State for 30 years, until he retired in 1954. He produced 32 scientific papers on botany and ecology.

Wells was an unusual botanist, however, who believed in popularizing his studies on plant communities, and spoke often over decades to garden clubs and schools.

Because of his influence, the Raleigh Garden Club early on had an interest and conservation bent that recognized firstly that the wildflowers, native plants, and “natural gardens” of the area were special. He promoted the novel idea that native plants could be incorporated into home gardens. He also convinced many gardeners in the Club that gardening needed to take environmental conditions into account – an early version of the saying “Right plant, right place.” This presages the garden world trend of today : gardening by partnering with Nature for a more ecological and healthier garden. He wanted his audience to see North Carolina as he did: a beautiful and majestic natural garden.

Edna Metz Wells was B.W.’s wife, and a member of the Raleigh Garden Club. She was also a science teacher at Broughton High School from 1929 on, as well as a serious academic and member of the NC Academy of Science, contributing significantly to its committee on high school science. In 1936 she earned her master’s degree from UNC, and was working on her Ph.D. in botany.

Wells and Edna were much like a modern couple, both pursuing careers. This was partly to Wells’ credit, as he believed women should find equal opportunity with men in the world of work. He also supported the idea that if a marriage was not successful, divorce was an acceptable solution. This generated quite a bit of criticism in a time when an instructor in college could be and was dismissed because he and his wife divorced. Wells also advocated birth control long before it was acceptable to do so, believing vehemently that children were to be loved, and if they could not be, then they should not be had. Many schools still required teachers to resign when they got married.

Charlotte Hilton Green was another RGC member, and the columnist for Our State magazine. In later life she was described as “the person most connected with ??? conservation in the State.” Her own garden was much influenced by BW Wells and was the first wildlife habitat garden.

The story of the Edna Metz Wells Park

Susan Iden, RGC founder, was an evangelist for wildflower gardening. She in turn was inspired by BW Wells. In 1927 the Club took over a 2-acre piece of unkept land along Clark St with the intention of creating a wildflower and native plants botanical garden. They called it Flora Park and in the first year alone they had planted 70 trees and 115 shrubs, and then transplanted in hundreds of wildflowers and native plants. They kept planting. In 1932 – 3, for example, they added 47 native azaleas and 10 of our native rhododendron, plus 41 flowering trees.

In 1937 Charlotte got the Science Club of Broughton HS to create a nature trail in the park. I’m guessing she called on Edna to work this out, although the written notes in our archives don’t mention it. They were both wives of NC State professors and Edna ran the Science Club. Also, Edna and her husband lived in a home overlooking the park and they both took their students there to study botany and native plants.

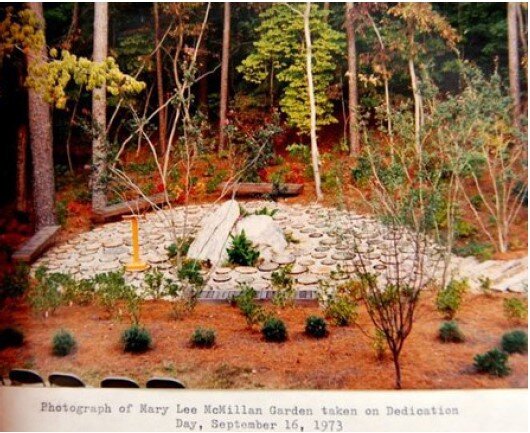

According to our RGC board minutes, Charlotte suggested that the park be renamed the Edna Metz Wells Park when Edna died suddenly in 1938 of complications from surgery after cancer. And Charlotte also recommended we donate the whole park to the city. But in the official request to the city council, our Club is not mentioned, and it is Edna’s students who request the city rename the park.

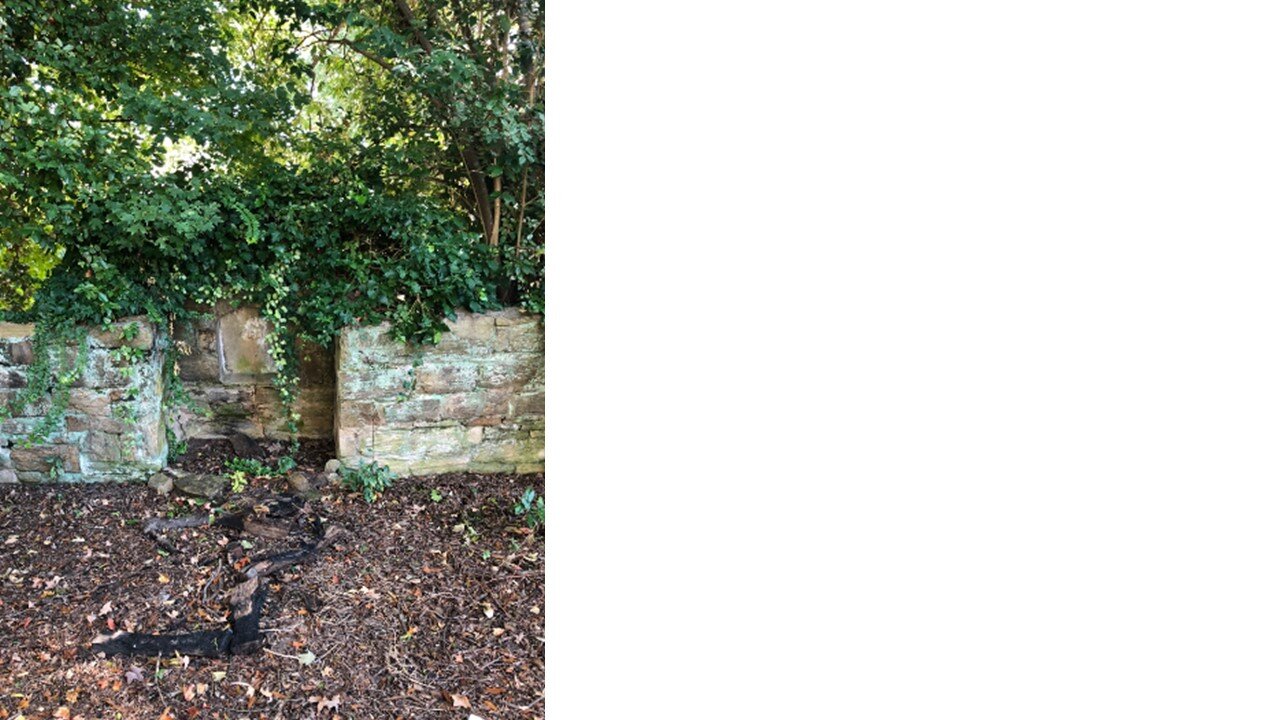

So here is an example of our forgotten history. If you go to the park, the sign describing the dedication makes no mention of RGC, or our work in creating and planting the park, nor even that we donated the park to the city.

Years later, in 1972-3 RGC planted 12 ornamental trees in the park. But it’s not only the Dept of Parks and Raleigh-ites who forget. If our members knew they were planting in one of our Club footprints, they didn’t acknowledge it in the 1973 meeting minutes. I believe we didn’t even realize by that time that we had a prior connection to this park. We had lost our own history.

Our member Laurie discovered this footprint! The park is relatively ignored … today it is overrun with invasive English ivy. I am heading there this spring to see if any of the wildflowers or flowering trees remain from the hard work of those early years. – at least some of the big trees should be there. I’ll report back in the Leaflet. And if any of you find something post pictures on our Facebook or send them to me.

BW Wells and the Raleigh Garden Club – Championing Native Plants and Ecology in Gardening

Wells probably had his biggest impact through his public talks and lectures to the Club, talks that continued for some 20 years. In 1935 he spoke at RGC’s garden school on “The ABC’s of Botany.” Other talks included “The Patchwork of North Carolina’s Great Green Quilt” and “The Most Remarkable Plant Community in North Carolina: The Big Savannah” and “The Wildflowers of North Carolina”. He spoke regularly at the monthly meetings, perhaps once every other year. He loved to talk and was a dynamic speaker. He was a wiry man, full of physical vigor as well. And his slides brought his subjects alive as well, as he was an artistic photographer and hand colored many of his photos.

Susan Iden and BW Wells were friends even before the RGC was founded. Together, they set up a wildflower show in 1920 at the Olivia Raney library. The flowers were displayed in baskets against a backdrop of pines and other greens.

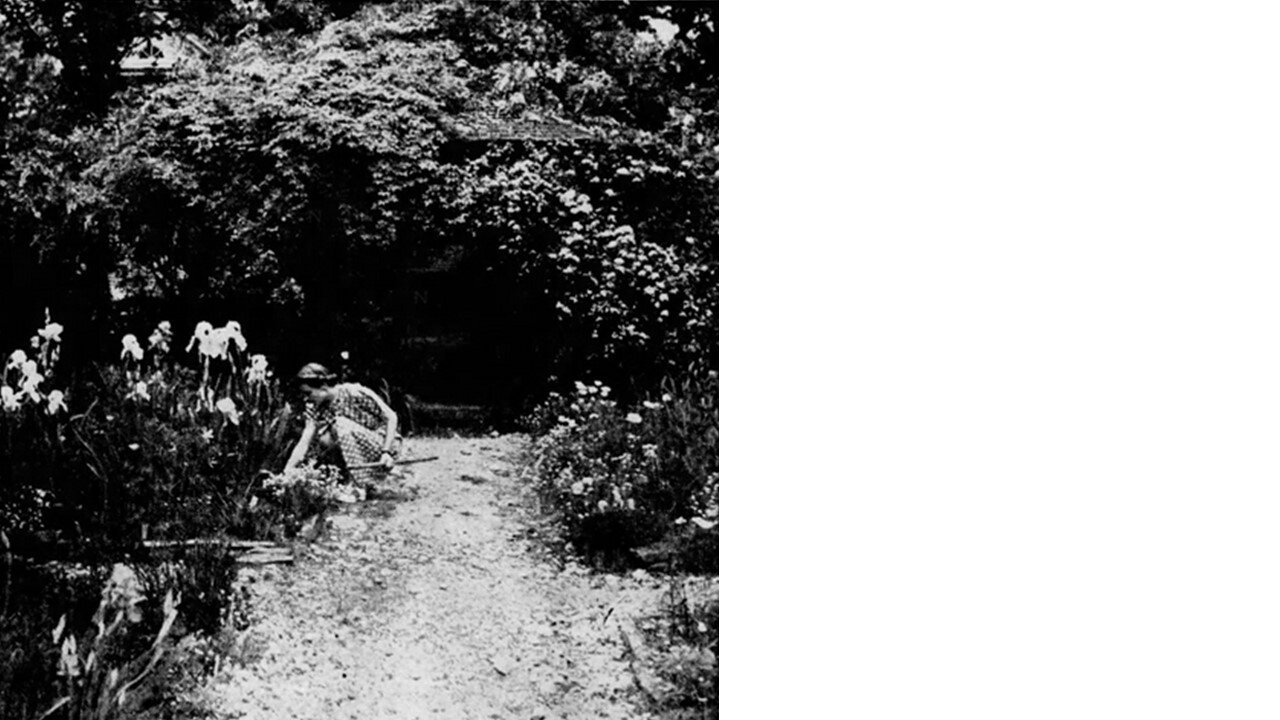

Susan herself was a devoted lover of the native wildflowers and woodlands in the Triangle and was much influenced by Wells ecological approach. Her own garden was a wildflower paradise. In one of her columns, she wrote: “I know of nothing that pays quite so much in pleasure and satisfaction in the garden as a wildflower bed. Wildflowers want no cultivation. Given a corner that halfway suits their habits of growth, a little shady and damp for most of them, and they will do the rest.”

The spring 1931 the RGC put on its first wildflower show in partnership with Wells and his botany department, and it was a big success, with hundreds visiting the show. Susan entered a large exhibit of over 25 species displayed in NC pottery. The show featured over 50 species of native plants, with a showy woodland garden display including trees, moss, rocks, and a miniature pool as the setting for clumps of wildflowers that were planted. After the show these plants found a permanent home in the Cameron Park Arboretum (now Edna Metz Wells Park). See transcript??? Wells and his botany department set this exhibit up, as well as classifying and labeling all the plants and the exhibits brought in. The Raleigh Times reported: “The educative side of the wild flower show has been emphasized, carrying out the principle of conservation for which the club stands.” Susan went on to make the Spring Wildflower Show a tradition from 19??? To ???

The following year, as RGC set up study groups for special interests in gardening, Susan Iden chaired one on native plants. They held "several hikes into the woods to study our wild flowers in their native habitats” with Wells leading the hikes.

In 1932 he led a hike to Hemlock Bluffs to study the plant community that is the remains of ancient glacial days. In 1940, Dr. Wells leads 3-day tour of natural gardens east of Raleigh, organized by Charlotte Hilton Green. She wrote a long article on the savannahs ( in clippings book).

A description of a typical Wells field trip by Susan Iden captures the flavor of these outings. In 1926, A group of fifteen persons left Raleigh in a caravan of 5 Model T Ford automobiles for a 2-day tour of Well’s favorite haunts in the coastal plain. Wells emphasized the topography of the landscape as well as the vegetation. Plant communities visited included a beech and maple forest, a pocosin (shrub-bog or bay) and the Big Savannah wildflower meadow. He also crammed in a swamp forest along the Cape Fear River, a freshwater marsh, a sand-ridge Turkey Oak stand, and ended with a beach party around a fire of driftwood.

Most people who got to go on his trips never forgot the experience. For one thing they were always crowded into several cars and carried out at an exhausting pace with many hikes to see as much as possible. And for another, Wells’ ability to share his observations ensured that everyone got an expanded view of nature and its intricate interrelationships. Susan wrote of the trip: “It was like having the scales lifted from eyes long dimmed by defective sight … the trip became a series of ever-changing plant communities and regions of progressive geological interest.” It was enlivening to experience Dr. Wells bringing us to “note the trees and flowers take on individuality and variety in their own plant communities, in what had heretofore been simply stretches of woods and fields with little to distinguish them from each other. “

His impact spread through the Club. Charlotte Hilton Green embraced the ecological approach enthusiastically, and created the first wildlife habitat garden at her home on White Oak Rd. She planted to support her lifelong love – the birds. And she frequently wrote of ecological matters in her columns -- get some examples…

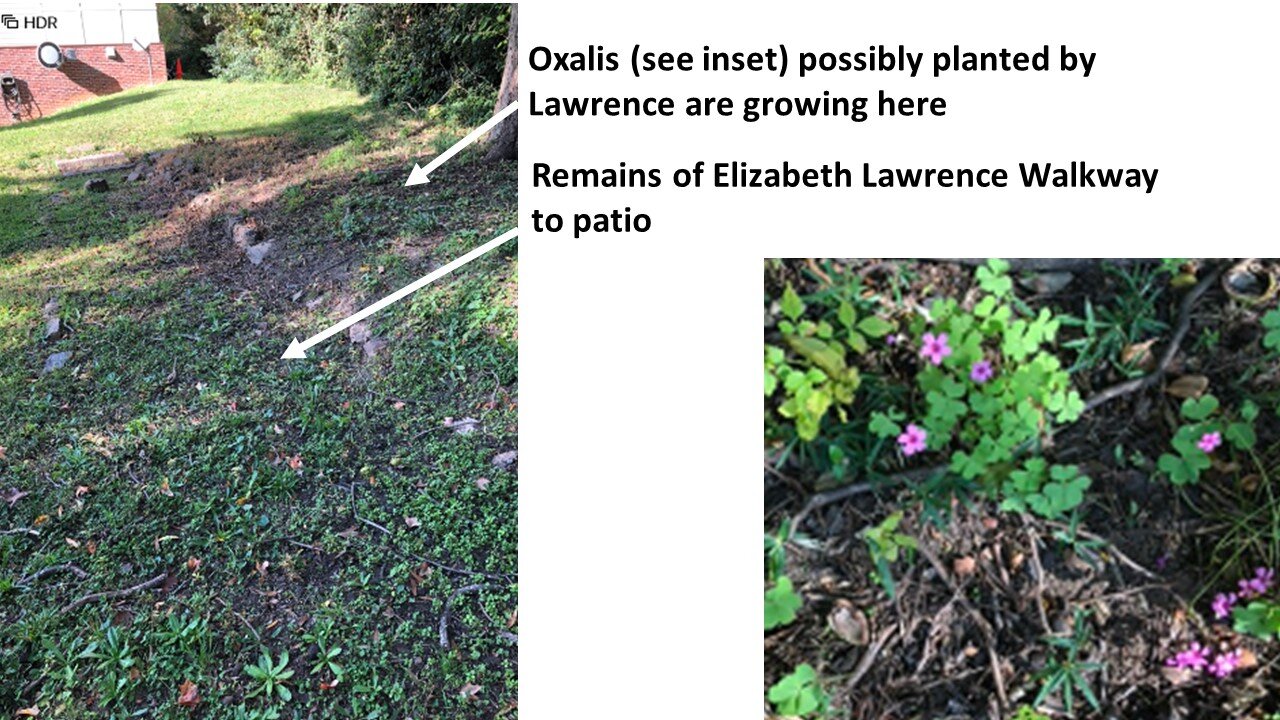

He taught Elizabeth Lawrence, who described his classes as her favorite in the curriculum of her master’s degree in landscape architecture.

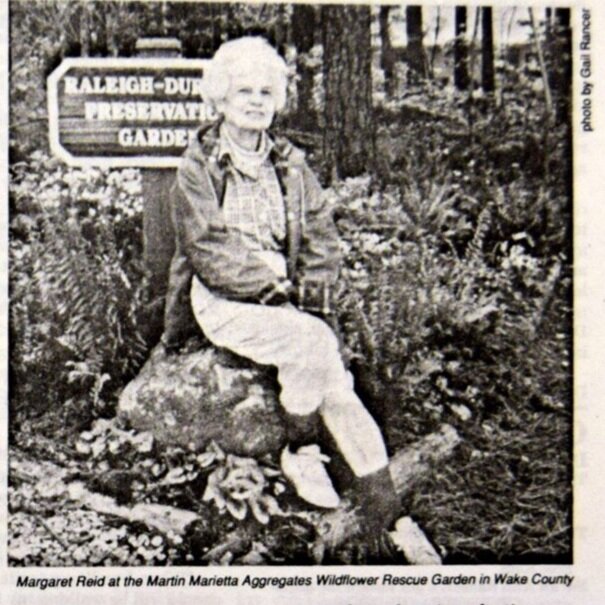

Perhaps his most fervent protégé was Margaret Reid. She was very much influenced by Wells through his talks at the garden club, and they became friends through her husband who also was at NC State. Wells and his wife Edna spent pleasant afternoons with the Reids, picnicking and studying unique plant communities in Wake County. Margaret arranged her garden in ecological plant communities, imitating what she saw in nature. She began rescuing plants from the path of development and planting them in her Raleigh garden as early as the 1930’s. Margaret’s garden has been preserved by the Triangle Land Conservancy and can still be enjoyed as an example of Wells style of gardening. Three of Wells’ plant communities have been protected and can still be visited in the Triangle today: Hemlock Bluff’s Nature Preserve and the Swift Creek Bluffs in Cary, White Pines Nature Preserve in Chatham County, and Flower Hill in Johnston County.

Wells’ last talk to the garden club was in the Club year of 1949-50, when he joined Charlotte for a talk on a special lecture on “Bird and Wildflower Groups.”

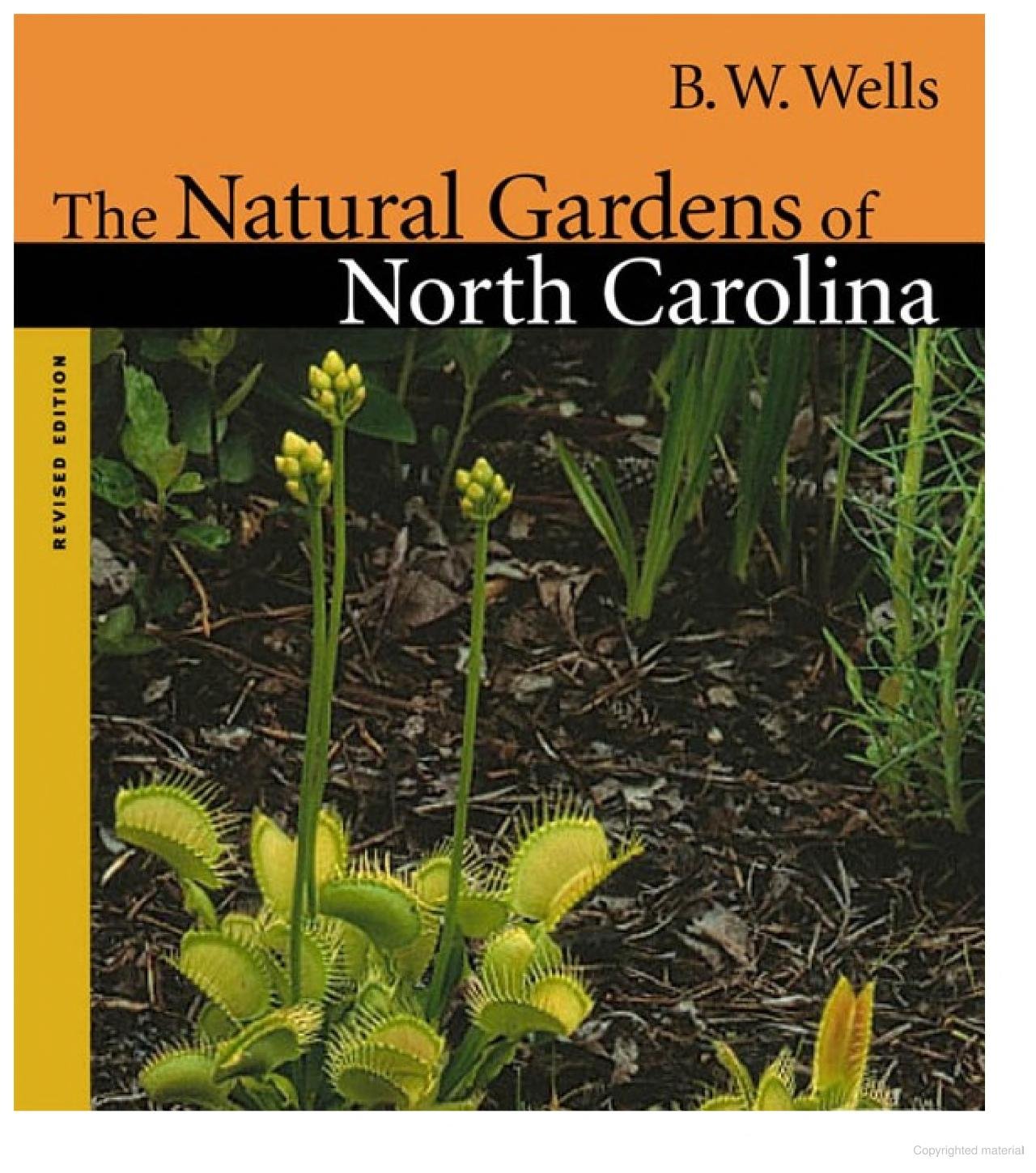

A Must-read Book for Anyone Interested in Wildflowers, Native Plants and Ecology

In 1932, Wells wrote The Natural Gardens of North Carolina to describe and explain to the state’s citizens the natural wonders Wells was studying and documenting as botany department chair at NC State. It was unusual because rather than listing plants by species, he organized it by describing “natural gardens” or ecosystems of plant communities occurring from the coast, the Piedmont and west to the mountains. He wanted to share and promote the beauty of North Carolina to gardeners and lovers of nature everywhere – not to the academic community. He was a pioneer advocate for using native plants in gardens.

The book was the brainchild of Susan Iden, and its publication was managed by her in her role as Conservation Chair of the GCNC. She was charged by the state GC to bring about a book on wildflowers by then President Ethel D. Tomlinson. Ethel recognized the need for a book on native NC wildflowers because of numerous requests for information received from local clubs and schools. There was no such book in print. She made Susan Conservation Chair with the sole objective of bringing such a book out. Susan was ideal because over a number of years her love of NC wildflowers had been demonstrated in articles about them in The Raleigh Times and also a column of hers was appearing at that time titled “Trailing the Wild Flowers” in the Charlotte Observer. Wells was of course the perfect author for such a book, and he agreed wholeheartedly and even agreed to take no compensation for writing it.

Financing the book was a challenge. It was Susan’s idea to sell advance copies through a subscription to all the state garden clubs. She was able to find a publisher in the UNC Press, though they put forth the proviso that the GC provide $1500 of the cost by selling 500 copies of the book. The Raleigh Garden Club helped, writing letters to publicize the book and setting up a subscription for club members to order it in advance. They also contributed $50, a considerable donation in those days. When the book was published, the RGC Board bought a copy to present to Susan Iden and another to add to the Club Library.

Matters proceeded well, until the bank failures of March 1932 due to the Great Depression included the bank that held the garden club funds for the book. All of their funds were lost. Ethel succeeded eventually in raising the money a second time, and Wells completed the book, working hard over vacations and weekends. It was ready for Christmas of 1932 – just barely! – and the publisher shipped the 500 copies using the GC list. The finished book was over 450 pages and held 225 photographs! Most of these were taken by Wells, but Susan Iden also contributed one, as did a few others.

The book was very well received and in fact made some money for the publisher, and royalties for Wells, which he generously donated the Garden Club of NC. But this would not have been certain at the time of Susan’s idea, and it is a credit to the publisher and to the garden club that both seized a way to provide the public with a “splendid contribution to Southern Horticultural literature.” It is a lasting legacy – for the book is still in print and still read today. It is considered a tour de force. Though its writing style is somewhat florid by today’s standards, Well’s evident sincerity and authentic exuberance, coupled with down-to-earth practicality, save the day and the reader is swept along for an education in NC ecology.

CONSERVATION EFFORTS

Wells fought directly for conservation, and worked with the garden club on protecting his beloved Big Savannah. As early as 1935, he asked RGC at one of his talks to sponsor a movement to take over the "great savannah" for a reservation or park. He continued working with the state garden club and many local ones, as well as environmental organizations. He was still urging it up until 1959, when it was plowed and destroyed forever.

But there is a wonderful sequel to that tragic moment. In the late 1990s, botanist Richard LeBlond with the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program was conducting natural area surveys in Pender County when he noticed an attractive group of flowers in the area underneath power lines. He returned to the site and realized that many of the unusual and rare species he saw were the same that Wells had documented on the Big Savannah. Further research showed that the two sites share the same unique soil type, and mowing by the power line owners had kept the habitat open, as fire had on Big Savannah.

Through a coordinated effort guided by the North Carolina Coastal Land Trust, representatives of the state, the university, and private individuals, as well as the Conservation Trust for North Carolina and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, worked to raise funds to purchase the 117-acre site from a cooperative landowner. In April 2002, it was dedicated and named B. W. Wells Savannah. Today, it supports a profusion of more than 200 documented species of wildflowers including orchids, carnivorous plants, and some rarities.

Although Wells was unable to save the Big Savannah, he was incredibly effective as a popularizer of what should be protected. He never lost his amazement and wonder and love of the plants of NC. A prophet for our views today, he believed widespread popular appreciation was the principal mechanism of preservation, stressing the importance of education the public to appreciate nature. His activism in this regard drove his hours devoted to face-to-face meetings, speaking to garden clubs and other groups whenever asked and leading hundreds of field trips to view the beauty of NC close up. His talks were always well received because his ideas and enthusiasm were stimulating and his delivery lively and even forceful.

Retirement and Rock Cliff Farm

Wells retired to Rockcliff Farm, and dedicated himself largely to his painting. The farm was preserved in his memory and was placed under the supervision of the BW Wells Association and the Dept of Parks and Recreation.

He was awarded posthumously by the NC Wildlife Federation Governor’s Award in Conservation Education, asserting “probably no one has done more to increase our appreciation of the beauties of nature and to foster conservation of plant life in the Southeast.” They called him “one of the most beloved and influential educators in NC.”